Newton’s First Law of Blogging:

Blogs at rest stay at rest,

Blogs in motion stay in constant motion,

unless either is acted upon by another force.

My blogging inertia was acted upon by a recent reminder (active mention on video) of my visit to Nashville which gave me time to hang out with our good Indycar friend George Phillips of Oilpressure.com and @oilpressureblog fame.

His gracious allowance of me as a guest on the recording of his “One Take Only” video segment, which appears on his blog, was a treat and a great and all-too-brief experience. Joining us was his original One Take Only counterpart, John McLallen and the three of us spent most of a gorgeous early-autumn Tennessee Saturday afternoon discussing all manner of things, but mostly the centering around Indycar.

After another “One Take Only” post, I reflected on my visit and noted how, despite our different points of view, we also need to remember and reinforce the commonalities shared as Indycar fans. Sequestered in relative solitude on George’s back patio, our various discussions, while not nearly as intense, did make me recall the John Hughes movie “The Breakfast Club” (which recently celebrated its 30th anniversary theatrical re-release) and how we fans may not be so dissimilar to the characters in that movie.

Perhaps writing a letter similar to Brian’s in the movie will also remind us of how we should not so easily let others or ourselves be defined by the various ‘entrenched encampments’ of Indycar fandom.

Mr. Indycar-Overlord,

We accept the fact that we had to sacrifice so many Saturdays and Sundays supporting Indycar, but we think you’re crazy to make us write a blog telling you who we think we are. You see us as you want to see us, in the simplest terms, the most convenient definitions. But what we found out is that each one of us is

a superfan,

a newbie,

a whiner,

an acolyte,

and a hyper-critic.

Does that answer your question?

Sincerely yours,

The Indycarfan Club

And now, It’s time for the Intermission…

And now, back again for the 2015 Indycar pre-season,

it’s DZ’s House of Indycar Megalomania!

(aka 2015 season predictions and strident drivel)

Oh, epochal and monolithic Indycar off-season. You are so coy.

With your belabored and long, somnombulant winter, you keep us in the doldrums until suddenly,

>BAM!<

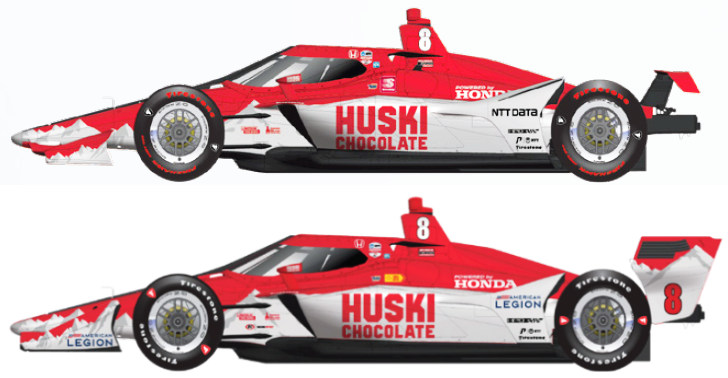

exploding forth a lush, verdant optimism for Indycar in the form of.. (dare I actually believe they’re here).. AEROKITS!

Technically 3 years late (or approximately 5.333 Indycar seasons stacked end-to-end), but here nonetheless. With the first discernible chassis diversity since the end of the 2008 season, Indycar has finally delivered on the concept approved in 2010, backed up along with new chassis until 2011, then slated for 2012, delayed until 2013, 2014.. ehhhrm, we’ve all been through that so no need to rehash it.

Regardless, aerokits are here and despite my 2011 predictions otherwise, I am pleasantly surprised at the difference in shape the Road/Street/ShortOval kits.

Dare I say it?

I dare.

I. Am. Satisfied.

And now for the grisly prediction bits.

(unofficially brought to you by the effects of Founder’s All-Day IPA)

2015

Biggest Storyline – Penske’s Chevys will dominate – to the point of becoming so oppressive, that they will become reviled. Robin Miller often says, ‘hate is good’ when referring to the fans’ predilection for seeking out a hero or villain in any contest. Whether he means to or not, Penske will become the Indycar version of the New England Patriots – the most disliked team outside of “PenskeNation”. Even ol’ Chippy will let his ego slide and actually play up his underdog status to ride the wave of anti-Penskeness. Roger and Tim maintain their ZFG (Zero F***s Given) ‘tude and happily cash the giant cardboard winner’s checks for 8 of the 16 races this season.

– Championship – Simon Pagenaud.

– Top 6 in points will be made up of 4 Penske drivers and 2 Ganassi.

– The Galactic Empire is strong and will keep the Rebel scum on the run.

It’s not as if Honda won’t be competitive, they will. They will just be lacking that tiny, tiny margin that takes one from finishing 8th to 1st. Honda wins just three races of the season, BUT one of them will be the Indy 500.

Rookie Of The Year – Stefano Coletti. Don’t ask me why, just know it came to me in a dream (All-Day IPA haze).

Biggest Darkhorse – TIE: James Jakes and Gabby Chaves. Don’t be surprised if you’re surprised when one of these drivers scores a podium this year.

Best Livery – If that Schmidt-Peterson Motorsport Spyder car becomes reality on the track, you can forget all you ever thought about the glory of retro liveries. That mo-chine looks simply badass.

Biggest Comeback – Simona de Silvestro. Of course she’s a fan favorite on a massively talented and well-funded team. She’ll struggle to see more than half of the races this season, but will not disappoint the faith placed in her by Andretti Autosport. Less than half the races and finishing 14th in points will be hard to reconcile. Just maybe AA finds a way to keep her in a seat all season long. If so, watch out.

Biggest Disappointment – The fans who align with the Legions of the Miserable. A season of dominance by one team will certainly lead to the chorus of boo-birds who will choose to again aim their venom at the overlords of Indycar for the disparity in racing. Their myopic views conveniently forget to accurately recall during the most heady days of CART in the 1980s, for example, despite a Gordy and Rick Ravon Mears most amazing Indy 500 finish in modern history, that 7th place Jim Hickman was a full 11 laps down at the finish. 7th place out of 33 racers – 11 laps down. Typically in those days, beyond the top 5 or so finishers there was the rabble of twenty or so others who had no chance of sniffing the podium. A singularly great finish but great overall quality, the events were generally not. Far too many fans, including one R. Miller, will further mire themselves in nostalgia for a time that was really less entertaining racing that what we’ll see in 2015. That is simply sad and I think the current sport deserves better.

With 10 of the 16 races non-ovals, and all of the major conflagrations occurring outside the ghostly hallows of influence that ovals once held, the high-water point for the new speedway kits be at their unveiling in Indy, May 3rd. Once May is over, the Speedway Oval kits get precious little use, in deference to the mighty cheese-graters of R/S/SO kits.

I really don’t expect much difference at all in the High Speed Oval kits and honestly (leads me to my Biggest Revelation), “it just doesn’t matter“.

Why do I say this?

Because, my friends, I’ve returned to this blog an enlightened man.

In my many winters of malcontent, discontent, and general dissatisfaction in the direction of Indycar in relation to its glorious past, I’ve given up hope. Sounds bleak perhaps, but I assure that it is not and I’ll tell you why.

For some unknown reason, my epiphanies have been many with regard to several sports since the last checkered flag flew for Indycar in 2014, one of which is giving up hope that Indycar will ever become anything closely resembling the past or having some gloriously innovative and wide-open future. Maybe I’m a late-comer to this method of thinking, especially compared to the 20-somethings/new guard who’ve never experienced first-hand a field of Offys and Drakes, Chevys and Cosworths, in glorious song and never will.

For better or worse, nothing can change the fact that the past shall always remain there and I’ve come to believe the nostalgia, no matter how well-meaning or beloved, is ultimately harmful to the sport of today. The ‘earth’ moved by the seismic rift that began with the formation of CART in 1979, and major aftershock of the formation of IRL in 1994, can never be repaired. The ground has irreparably been shifted. So to history it all shall be laid anyway. Indycar must promote the here and now, and forget trading on past glory which always lends to irritating old wounds.

It’s a time to heal.

I’ve changed.

I’ve reconciled (finally) with Indycar never being the hallmark of innovation and brutal speed that it once was.

I’ve accepted that the glories past can never be recreated, and that they shouldn’t be.

I see many things on the horizon for Indycar that will give me much entertainment and satisfaction, when I don’t look at it from the immensely-removed perspective that includes anything prior to the last 10 years of Indycar.

I’ve embraced the belabored arrival of the aerokits.

I’ve finally made my peace with saying goodbye to the old Indycar.

I’ve become a happier race fan for it.

I predict I’m going to love watching Indycar unfold this season, and I know that’s one prediction I won’t miss.