There is a moment when renewing one’s Indy 500 tickets each year that is bitter and sweet, but seems to shade a bit more to the bitter side. Once again we catch our breath from a race that we love for the moments of breath it draws from us, only to return to a sense of normalcy and realize we’re over 350 days away from the next 500.

As tradition is a hallmark of the Indy 500, I return to the annual numbing coolness of bland columns and rows of race statistics to soothe a head that aches with restarting the 51-week cycle of anticipation all over again. First, let’s have a quick look back at my experience of this year’s classic.

The 2023 Race Weekend – Rather unexpectedly, and without a definite cause to my knowledge, there was a definite sensation that the attendance at IMS events during race weekend was notably higher than recent years and nearly paralleled 2016. Race day especially, and 2016 aside, there were more people at the track earlier than I’ve seen in a long time. When I really think about it, I may have to go back to the mid-1990s, but with so much of the event schedule changed since, it’s difficult to compare.

Welcome Race Fans! – Many of you likely already are aware of my race-day alter-ego and friends who join in the fun. As we are basically just average people, we strive to be approachable and are more than happy to take pictures with other race fans. Our primary desire, to extend goodwill and positive vibes on raceday, is especially enjoyable when we encounter people who reveal that this is their first race. This year we also encountered a greater number of race virgins than in years past and we welcome them and try to celebrate them just for being at IMS. Hopefully we added to their enjoyment of raceday. Also new to our seating section were two fans who’ve never been and while it’s comforting to see those make the pilgrimage each year, it’s also a positive sign to meet and interact with new fans who are often awed by all of it. It truly is a world-class, mega-sporting event.

We also met a good number of international fans again and we’re only happy to wish them well and hope they come back again. Our international list keeps growing and meeting fans from Wales, Denmark, and Sweden were new additions.

I’m willing to keep this silliness up as long as I have my crew with me, although we were diminished a bit as Mr. Bricks was out this year due to injury. He was missed by us and by fans alike who’ve seen us in years past. Hopefully he can make a full recovery for 2024.

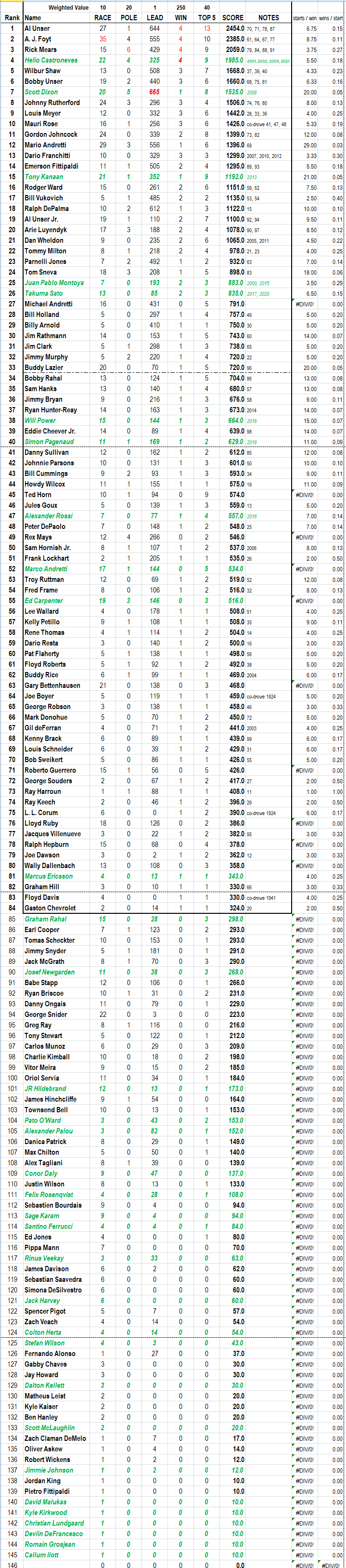

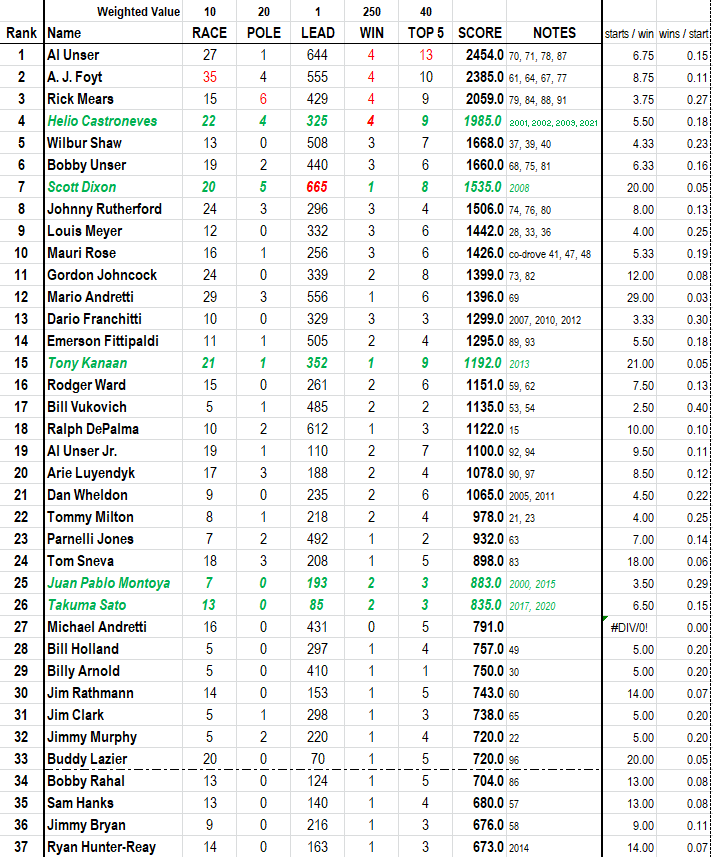

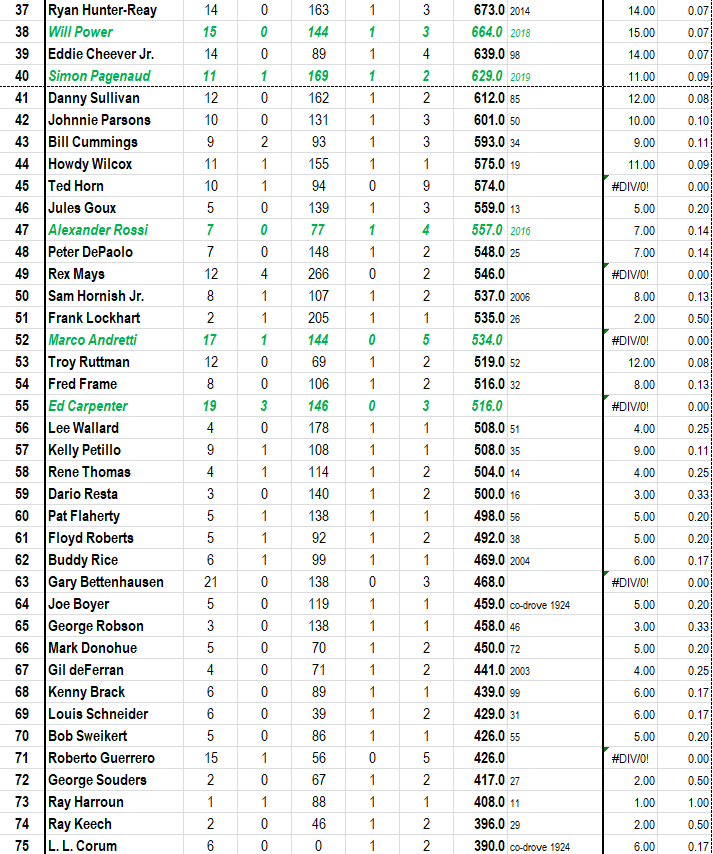

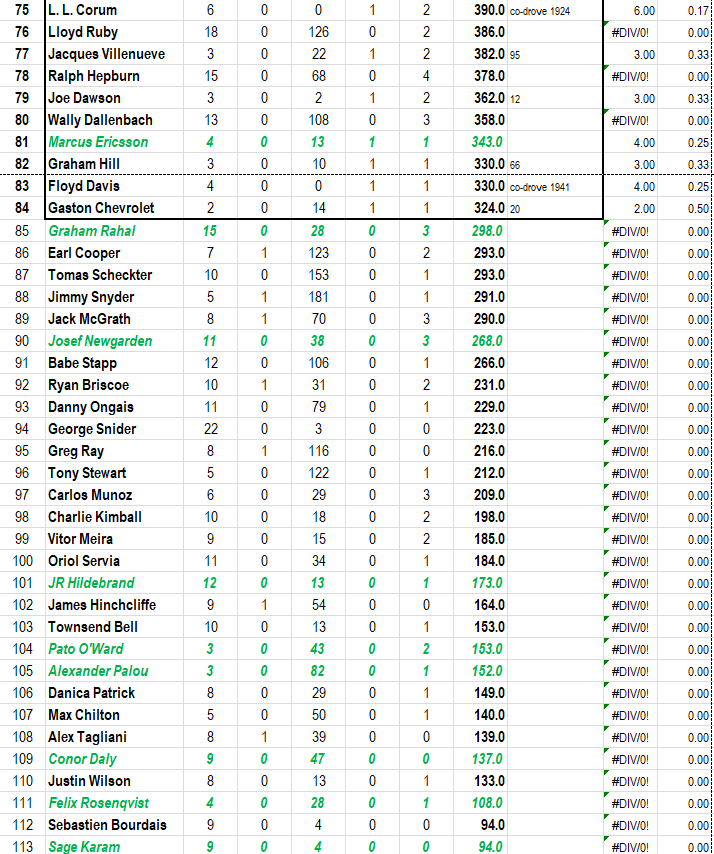

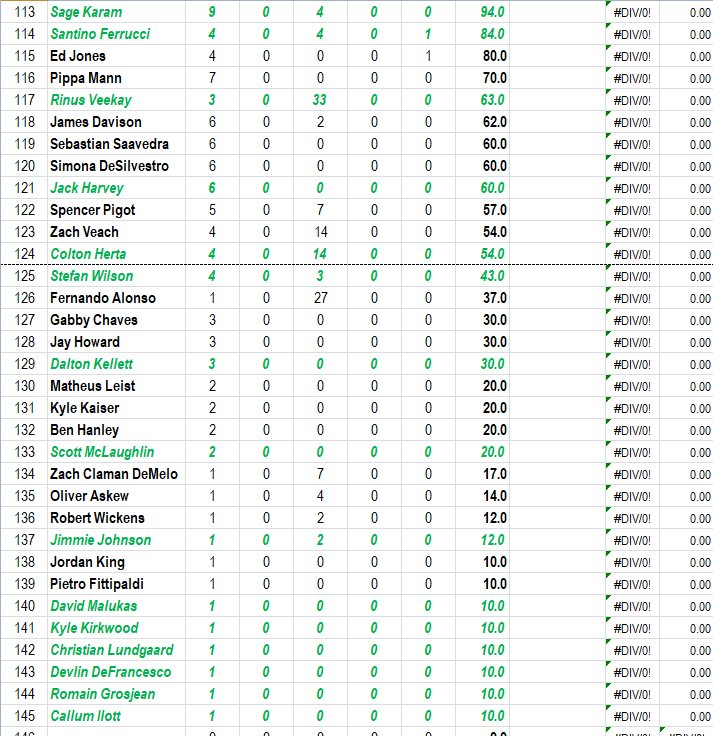

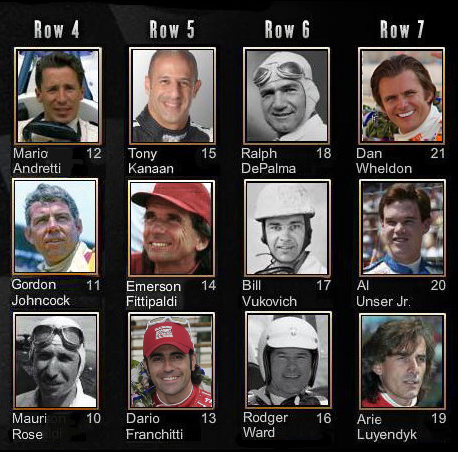

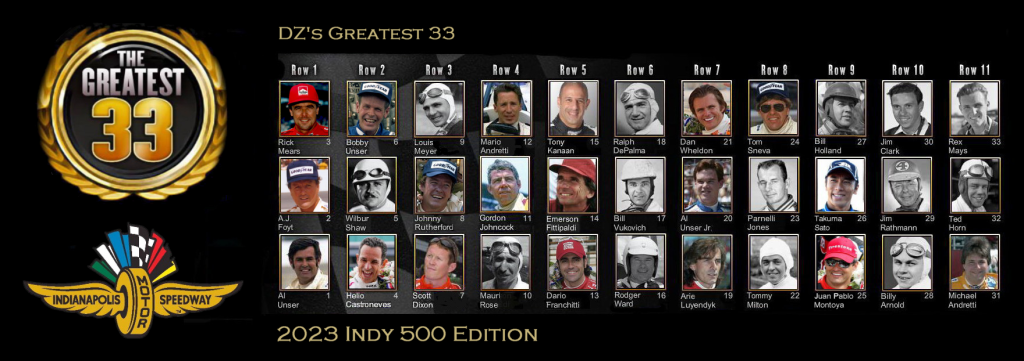

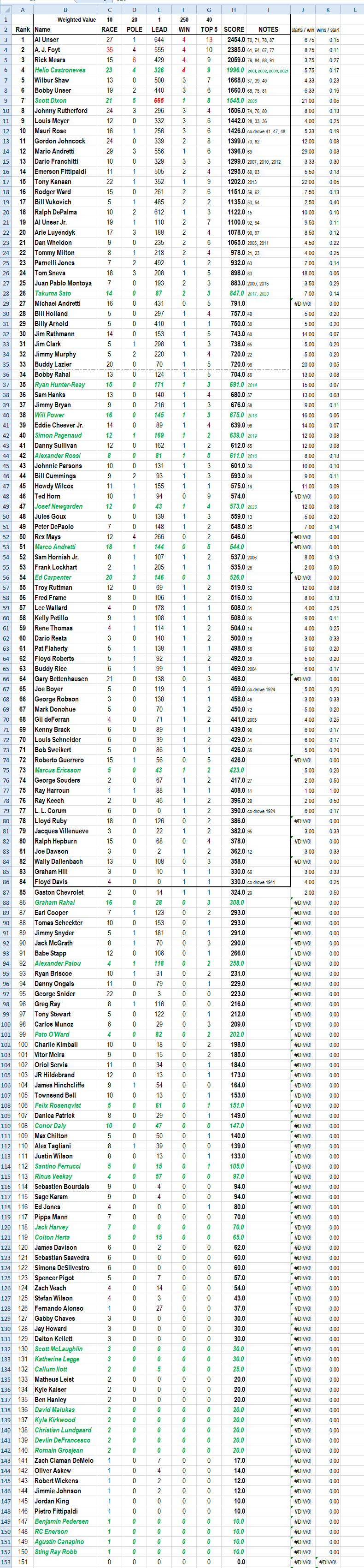

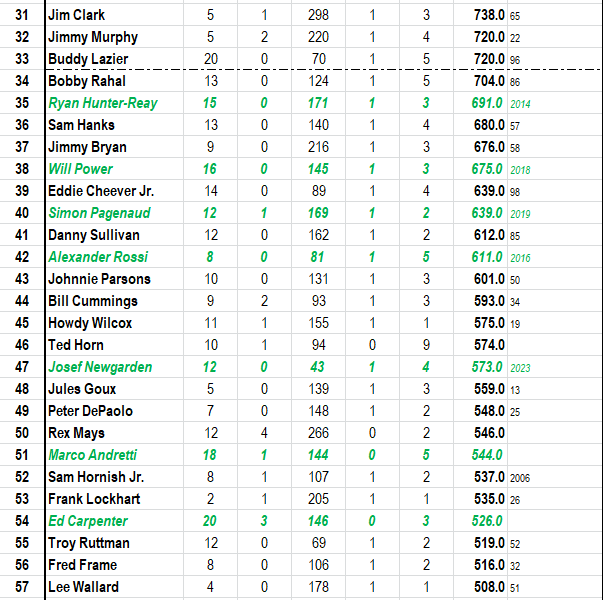

The Greatest 33 – As a quick refresher, IMS put out this list for the 100th anniversary in 2011 and fans could vote on their Greatest 33 drivers of the Indy 500. Wanting to put more than a cursory and superficial effort in choosing, I created a select batch of statistics to help make my choices then and since have maintained this list every year via a spreadsheet with annual updates based on results. Active drivers after the Indy 500 are shown in green. When time permits, I’ll consider adding a category for Total Miles Completed and updating the list, but until then, here it is in all it’s row-and-column insouciance:

All active drivers gained another 10 points for another race start plus one point for any lap lead this year. Palou’s Pole position pushed him up the list and Newgarden’s win of course vaults him up the leaderboard, as most of the notable movement comes from mid-list. As it stands, Dixon remains the highest scoring single-winner on my Greatest 33.

The Last Row Party – Some may notice the last three faces in my Greatest 33. The list is essentially a top 30 plus the 3 best to never win it. In an homage to the Indianapolis Press Club Foundation Last Row Party, the 11th Row consisting of Michael Andretti, Ted Horn, and Rex Mays currently occupy it. Essentially this leaves Clark on the ’30th place bubble’ for winners of the 500. It also takes very little to see how the lone remaining active Andretti could join that row.

Very little changed at the top of the sheet this year, but it gets quite a bit more interesting with the gaggle of drivers hovering at the ‘cut-line’. As current non-winners go, if Marco races just once more and not win, he’ll supplant Rex Mays in the 33rd spot. If he wins, however, his minimum points haul of 301 to his current 544 would elevate him into 27th, trailing Takuma Sato and bumping everyone behind, including Jim Clark out of the top 30, and off my Greatest 33 list. Here’s the standings around the cut-line:

As you can see, there are several active drivers around Marco who stand to make a big jump as well should the racing gods favor them with the next 500 win. A first win for Carpenter, or second wins for Newgarden, Rossi, Pagenaud, Power, and Hunter-Reay would see them join my Greatest 33.

Winner, Winner – The checkers fell to the newest first-time winner – Josef Newgarden. The nature of my list shows that winning is a huge points premium so my Greatest 33 list contains all multiple winners of the Indy 500. Being a one-time winner doesn’t begin to meet the elite of the list without having many races, poles, and laps lead to distinguish them.

In total, 75 drivers have won the 500 – 55 are one-time winners and 20 are multiple time winners accounting for 54 (basically half) of the 107 races run. Top 5 finishes for Newgarden, Ericsson, Ferrucci, Palou, and Rossi all boosted their standings. .

Miscellany – One thing I miss most about the new scoring pylon versus the old one is the average race speed shown at the top of the stack. The Indy 500 qualifying field surpassed the previously quickest qualifying field of 2022. In addition, the weather was just gorgeous for raceday, so the conditions existed to have a race among the fastest as well. With an average speed of 168.193 and clocking in at 2:58:21.9611, it was the 10th fastest race of all time, including 27 laps of yellow and three red flag delays. Not coincidentally, the fastest race of all-time in 2021 had the fewest laps under yellow with 18, and no red-flags.

In Conclusion – The drivers in the Greatest 33 change very little, although several of the youthful and newest generation of Indycar drivers look set to march steadily up this legendary list. Can the established guard hold onto their dominance or will a new wave begin to make their presence known on an annual basis? Newgarden’s win as a bridge member between the younger and older generations perhaps suggests, as does the officially-official (seeming) retirement of TK, that the new wave is here to stay and will begin to put their mark on this great event.

Time is running out for the current greats, but unlike generations many years ago, they still have competitive equipment and will be contenders as long as they’re able and willing to try. This sets us up for great races in the years to come and, perhaps even more now, I can’t wait for the next 500. Which active driver would you like to see pop up into The Greatest 33?