“Days turn to minutes and minutes to memories,

Life sweeps away the dreams we have planned.

You are young and you are the future,

so suck it up and tough it out,

and be the best you can…”

J. Mellencamp, 1985

As this Indycar fans ages, it becomes evermore disturbing just how time seems to not only pass more quickly but at an accelerating rate. Some of you may already experience this, and some soon will, but it seems no one is immune to this sensation.

Johnny Cougar, who in his evolving artistic maturity became John Mellencamp, also noted this phenomenon in several songs during and after the apogee of his career (in terms of sales). The lyric quoted above is taken from the Scarecrow album song entitled, ‘Minutes To Memories’.

I first experienced that lyric and the songs of the Scarecrow album during a time in my life that I can scarcely recall anymore – my early adulthood, aged 18, and moving away from my home, to college in Indianapolis. Painfully familiar with how my friends’ parents always took a bittersweet tone when they sang along with a similar lyric from his notable ‘Jack and Diane’ song three years prior, I was already aware that one coping mechanism is to try to remain blissfully unaware of my own impending life changes, holding onto 16 as long as I can.

Much as we all perhaps seek to maintain grasp on that frightfully short (and often easiest) portion of our life, change comes at our behest or otherwise and more often than not, different than we imagined. I’m sure Anton George would likely attest.

So too it was with the world of Indycar, ten years ago in 2010.

“TEN YEARS, MAN! Ten. Ten YEARS?! Ten years. TEN… TEN.. YEAARRRRRSSS! Ten years!” One of my favorite scenes from the movie Grosse Point Blank comes to mind immediately whenever we near an anniversary or some numerical decade involving a base-10 reflection leads to the incredulity of how quickly that time has passed by us.

On January 1 of 2010, the landscape of Indycar was a fair bit different.

- IZOD had recently agreed to become the first title sponsor of Indycar since Northern Lights ended after 2001.

- Tony George would resign in mid-January of 2010 from the Board of Directors of IMS, following a very long, protracted, and expensive battle with CART/ChampCar, that resulted in the absorption of that sanction and teams into the new IZOD IndyCar Series.

- February 2nd saw the hiring of Randy Bernard as the new CEO of the Indy Racing League, the single-most prominent division of the IndyCar Series and open-wheel racing in the US.

- Names familiar to us now populated the drivers and ownership rosters. Names like Penske, Ganassi, Andretti, Foyt, and Coyne, all owned at least one full-time entry.

- Kanaan, Marco, RHR, Dixon, Grahamie, Sato-san, Easy Ed Carpenter, Power, and Helio all raced along the other famous names who no longer ply their trade such as; Meira, Danica, Franchitti, Bad-Ass Wilson, Wheldon, Fisher, and Briscoe inferno, and many others.

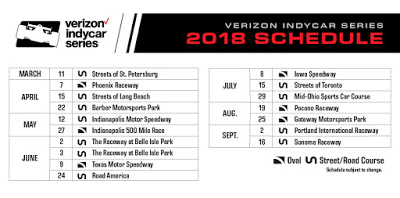

- The schedule included 17 events with currently-familiar Indycar homes such as; St. Pete, Barber, Long Beach, Indy, Texas, Iowa, Toronto-eh, and Mid-Ohio. The venues of 2010 not on the 2020 schedule may jog some memories; Sao Paulo, Kansas, The Glen, Edmonton, Infiniyawn, Chicagoland, Kentucky, Motegi, and Homestead.

- Honda , set to exit Indycar after 2009 was sufficiently cajoled into staying through 2011.

- Early into an interminable 10-year and fractured TV deal, ABC/ESPN and Versus split the schedule.

- An oval (Foyt) trophy and road/street (Andretti) trophy was awarded at the end of 2010 along with THIS newly-minted (thankfully short-lived) and spuriously-conceived ‘Flying Cocksman’ IZOD-commissioned Series Championship trophy:

How no one has grabbed a modern OneWheel board and dressed like this trophy, no matter how ironically, to the 500, or the final race of the Indycar Championship is beyond me.

Set in motion in 2010, however, were several things which we now find more enjoyable about Indycar to this day (many of which couldn’t arrive too soon for fans):

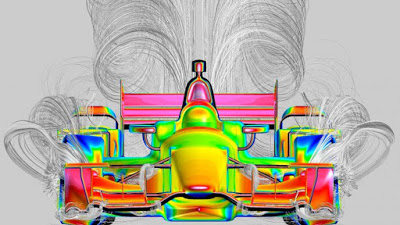

- New chassis development with updates and more attractive features.

- A severe dislike of the aforementioned split TV schedule (e-NOUGH of the splits already!) which lead to a single-network-supplier TV package in 2019 (So sorey-eh to my Canadian friends though!)

- Dedicated work toward multiple engine manufacturers and MORE POWAH!

- A newfound enthusiasm for the sport stemming from an executive who openly-engaged the fans (somewhat to his own peril). He and the league worked to incorporate their desires into the product (much-easier it is now for fans to be heard for the TV supplier, venues, and the league than ever before). Not all data is important, but the mere act of accepting and sifting through modern consumer-input allowed a growth into a more fan-centric product as ever before, I believe.

- Shift away from the purely traditional schedule and dates, and more toward keeping more financially-successful events on the schedule, developing continuity from there. As much as we all loved Milwaukee or Chicagoland or Kansas or The Glen, the pure fact remains that not enough paying race fans came through the doors, regardless of marketing or myriad other excuses.

In looking back at the world of Indycar in 2010, there are many familiar things, yet the sport has changed quite a bit in what doesn’t seem 10 years.

I started this blog in late-2009 and, likewise, it doesn’t seem to be that terribly long ago, yet in many ways, at 52 years old, I feel too old to be a voice of the modern Indycar fan.

In taking most of 2019 off from blogging here, I reflected on Indycar bloggers and podcasters past and present. Is there a place for me to keep some moderate/centrist/devil’s advocate/grounded thoughts and ideas ‘out there’ for Indycar and autosport fans? Is it of any value and effort in an increasingly binary society? Is examining alternative ideas and keeping a modicum of basic critical thought toward this sport something enjoyable? Is anyone already doing this and much better than I? I’ve decided to find out.

In doing so, I also relocated to my blog to this new site, which may undergo changes as I become more familiar with formatting and the like. I do not undervalue how an aesthetically pleasing site is more enjoyable, so bear with me as things become less utilitarian and more eye-friendly. I’ve also brought forward the posts from my previous site for my reference as much as anyone else’s. Some posts seem cringeworthy today, but I suppose it’s no different than looking back in an old yearbook at pictures that captured the moment with an accuracy we may now wish it hadn’t.

I’m not young, nor the future, but I’m going to suck it up, tough it out, and be the best I can.

I welcome your feedback here in the comments, via twitter @groundedeffects, or via my email groundedeffects@gmail.com, and look forward to interacting with you here or maybe even at an Indycar track in 2020. Happy New Year!